At the end of January, Washington, DC, saw an extremely unusual event. The MAHA Institute, which was set up to advocate for some of the most profoundly unscientific ideas of our time, hosted leaders of the best-funded scientific organization on the planet, the National Institutes of Health. Instead of a hostile reception, however, Jay Bhattacharya, the head of the NIH, was greeted as a hero by the audience, receiving a partial standing ovation when he rose to speak.

Over the ensuing five hours, the NIH leadership and MAHA Institute moderators found many areas of common ground: anger over pandemic-era decisions, a focus on the failures of the health care system, the idea that we might eat our way out of some health issues, the sense that science had lost people's trust, and so on. And Bhattacharya and others clearly shaped their messages to resonate with their audience.

The reason? MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) is likely to be one of the only political constituencies supporting Bhattacharya's main project, which he called a "second scientific revolution."

In practical terms, Bhattacharya's plan for implementing this revolution includes some good ideas that fall far short of a revolution. But his motivation for the whole thing seems to be lingering anger over the pandemic response—something his revolution wouldn't address. And his desire to shoehorn it into the radical disruption of scientific research pursued by the Trump administration led to all sorts of inconsistencies between his claims and reality.

If this whole narrative seems long, complicated, and confusing, it's probably a good preview of what we can expect from the NIH over the next few years.

MAHA meets science

Despite the attendance of several senior NIH staff (including the directors of the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) and Bhattacharya himself, this was clearly a MAHA event. One of the MAHA Institute's VPs introduced the event as being about the "reclaimation" of a "discredited" NIH that had "gradually given up its integrity."

"This was not a reclamation that involved people like Anthony Fauci," she went on to say. "It was a reclamation of ordinary Americans, men and women who wanted our nation to excel in science rather than weaponize it."

Things got a bit strange. Moderators from the MAHA Institute asked questions about whether COVID vaccines could cause cancer and raised the possibility of a lab leak favorably. An audience member asked why alternative treatments aren't being researched. A speaker who proudly announced that he and his family had never received a COVID vaccine was roundly applauded. Fifteen minutes of the afternoon were devoted to a novelist seeking funding for a satirical film about the pandemic that portrayed Anthony Fauci as an egomaniacal lightweight, vaccines as a sort of placebo, and Bhattacharya as the hero of the story.

The organizers also had some idea of who might give all of this a hostile review, as reporters from Nature and Science said they were denied entry.

In short, this was not an event you'd go to if you were interested in making serious improvements to the scientific method. But that's exactly how Bhattacharya treated it, spending the afternoon not only justifying the changes he's made within the NIH but also arguing that we're in need of a second scientific revolution—and he's just the guy to bring it about.

Here's an extensive section of his introduction to the idea:

I want to launch the second scientific revolution.

Why this grandiose vision? The first scientific revolution you have... very broadly speaking, you had high ecclesiastical authority deciding what was true or false on physical, scientific reality. And the first scientific revolution basically took... the truth-making power out of the hands of high ecclesiastical authority for deciding physical truth. We can leave aside spiritual—that is a different thing—physical truth and put it in the hands of people with telescopes. It democratized science fundamentally, it took the hands of power to decide what's true out of the hands of authority and put it in the hands of ridiculous geniuses and regular people.

The second scientific revolution, then, is very similar. The COVID crisis, if it was anything, was the crisis of high scientific authority geting to decide not just a scientific truth like "plexiglass is going to protect us from COVID" or something, but also essentially spiritual truth. How should we treat our neighbor? Well, we treat our neighbor as a mere biohazzard.

The second scientific revolution, then, is the replication revolution. Rather than using the metrics of how many papers are we publishing as a metric for success, instead, what we'll look at as a metric for successful scientific idea is 'do you have an idea where other people [who are] looking at the same idea tend to find the same thing as you?' It is not just narrow replication of one paper or one idea. It's a really broad science. It includes, for instance, reproduction. So if two scientists disagree, that often leads to constructive ways forward in science—deciding, well there some new ideas that may come out of that disagreement

That section, which came early in his first talk of the day, hit on themes that would resurface throughout the afternoon: These people are angry about how the pandemic was handled, they're trying to use that anger to fuel fundamental change in how science is done in the US, and their plan for change has nearly nothing to do with the issues that made them angry in the first place. In view of this, laying everything out for the MAHA crowd actually does make sense. They're a suddenly powerful political constituency that also wants to see fundamental change in the scientific establishment, and they are completely unbothered by any lack of intellectual coherence.

Some good

The problem Bhattacharya believes he identified in the COVID response has nothing to do with replication problems. Even if better-replicated studies ultimately serve as a more effective guide to scientific truth, it would do little to change the fact that COVID restrictions were policy decisions largely made before relevant studies could even be completed, much less replicated. That's a serious incoherence that needs to be acknowledged up front.

But that incoherence doesn't prevent some of Bhattacharya's ideas on replication and research priorities from being good. If they were all he was trying to accomplish, he could be a net positive.

Although he is a health economist, Bhattacharya correctly recognized something many people outside science don't: Replication rarely comes from simply repeating the same set of experiments twice. Instead, many forms of replication happen by poking at the same underlying problem from multiple directions—looking in different populations, trying slightly different approaches, and so on. And if two approaches give different answers, it doesn't mean that either of them is wrong. Instead, the differences could be informative, revealing something fundamental about how the system operates, as Bhattacharya noted.

He is also correct that simply changing the NIH to allow it to fund more replicative work probably won't make a difference on its own. Instead, the culture of science needs to change so that replication can lead to publications that are valued for prestige, job security, and promotions—something that will only come slowly. He is also interested in attaching similar value to publishing negative results, like failed hypotheses or problems that people can't address with existing technologies.

The National Institutes of Health campus.

Credit:

NIH

Bhattacharya also spent some time discussing the fact that NIH grants have become very risk-averse, an issue frequently discussed by scientists themselves. This aversion is largely derived from the NIH's desire to ensure that every grant will produce some useful results—something the agency values as a way to demonstrate to Congress that its budget is being spent productively. But it leaves little space for exploratory science or experiments that may not work for technical reasons. Bhattacharya hopes to change that by converting some five-year grants to a two-plus-three structure, where the first two years fund exploratory work that must prove successful for the remaining three years to be funded.

I'm skeptical that this would be as useful as Bhattacharya hopes. Researchers who already have reason to believe the "exploratory" portion will work are likely to apply, and others may find ways to frame results from the exploratory phase as a success. Still, it seems worthwhile to try to fund some riskier research.

There was also talk of providing greater support for young researchers, another longstanding issue. Bhattacharya also wants to ensure that the advances driven by NIH-funded research are more accessible to the public and not limited to those who can afford excessively expensive treatments—again, a positive idea. But he did not share a concrete plan for addressing these issues.

All of this is to say that Bhattacharya has some ideas that may be positive for the NIH and science more generally, even if they fall far short of starting a second scientific revolution. But they're embedded in a perspective that's intellectually incoherent and seems to demand far more than tinkering around the edges of reproducibility. And the power to implement his ideas comes from two entities—the MAHA movement and the Trump administration—that are already driving changes that go far beyond what Bhattacharya says he wants to achieve. Those changes will certainly harm science.

Why a revolution?

There are many potential problems with deciding that pandemic-era policy decisions necessitate a scientific revolution. The most significant is that the decisions, again, were fundamentally policy decisions, meaning they were value-driven as much as fact-driven. Bhattacharya is clearly aware of that, complaining repeatedly that his concerns were moral in nature. He also claimed that "during the pandemic, what we found was that the engines of science were used for social control" and that "the lockdowns were so far at odds with human liberty."

He may be upset that, in his view, scientists intrude upon spiritual truth and personal liberty when recommending policy, but that has nothing to do with how science operates. It's unclear how changing how scientists prioritize reproducibility would prevent policy decisions he doesn't like. That disconnect means that even when Bhattacharya is aiming at worthwhile scientific goals, he's doing so accidentally rather than in a way that will produce useful results.

This is all based on a key belief of Bhattacharya and his allies: that they were right about both the science of the pandemic and the ethical implications of pandemic policies. The latter is highly debatable, and many people would disagree with them about how to navigate the trade-offs between preserving human lives and maximizing personal freedoms.

But there are also many indications that these people are wrong about the science. Bhattacharya acknowledged the existence of long COVID but doesn't seem to have wrestled with what his preferred policy—encouraging rapid infection among low-risk individuals—might have meant for long COVID incidence, especially given that vaccines appear to reduce the risk of developing it.

Matthew Memoli, acting NIH Director prior to Bhattacharya and currently its principal deputy director, shares Bhattacharya's view that he was right, saying, "I'm not trying to toot my own horn, but if you read the email I sent [about pandemic policy], everything I said actually has come true. It's shocking how accurate it was."

Yet he also proudly proclaimed, "I knew I wasn't getting vaccinated, and my wife wasn't, kids weren't. Knowing what I do about RNA viruses, this is never going to work. It's not a strategy for this kind [of virus]." And yet the benefits of COVID vaccinations for preventing serious illness have been found in study after study—it is, ironically, science that has been reproduced.

A critical aspect of the original scientific revolution was the recognition that people have to deal with facts that are incompatible with their prior beliefs. It's probably not a great idea to have a second scientific revolution led by people who appear to be struggling with a key feature of the first.

Political or not?

Anger over Biden-era policies makes Bhattacharya and his allies natural partners of the Trump administration and is almost certainly the reason these people were placed in charge of the NIH. But it also puts them in an odd position with reality, since they have to defend policies that clearly damage science. "You hear, 'Oh well this project's been cut, this funding's been cut,'" Bhattacharya said. "Well, there hasn't been funding cut."

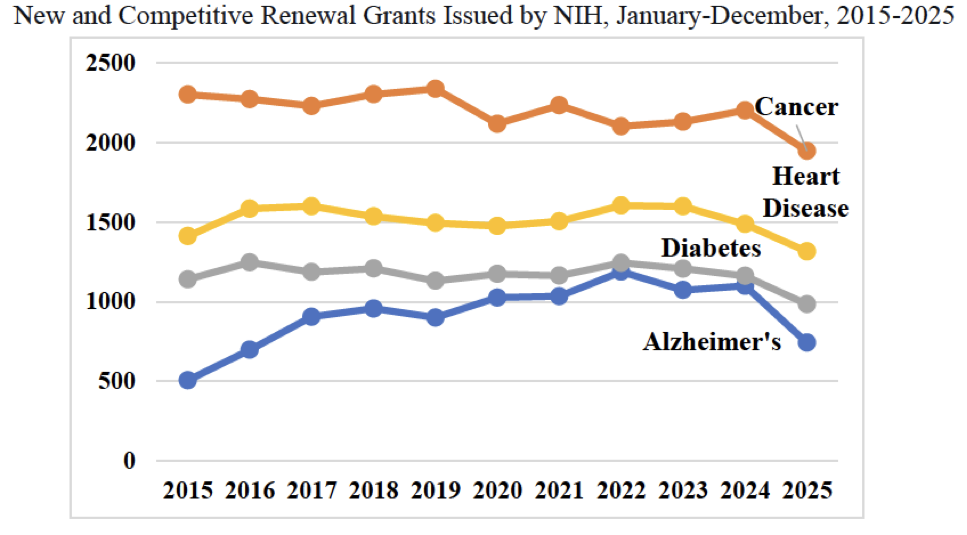

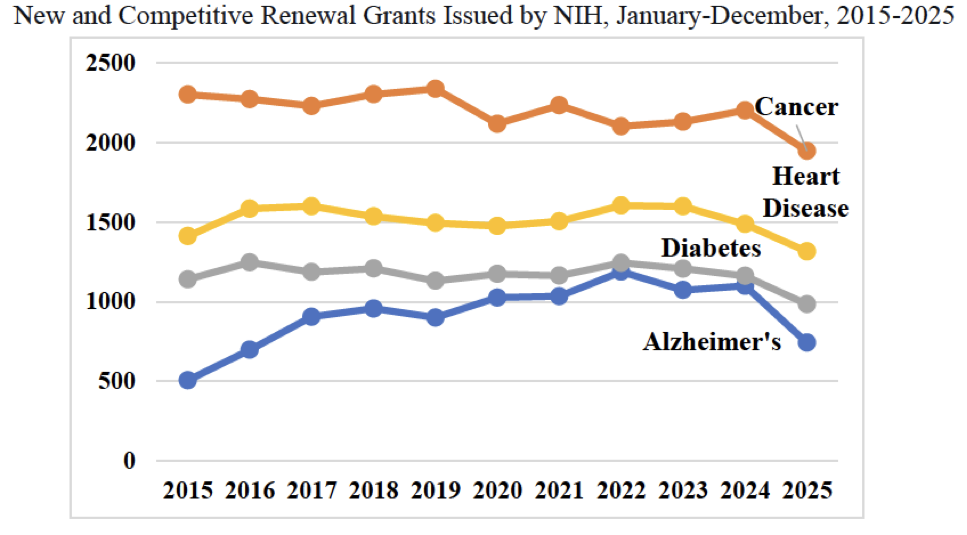

A few days after Bhattacharya made this statement, Senator Bernie Sanders released data showing that many areas of research have indeed seen funding cuts.

Bhattacharya's claims that no funding had been cut appears to be at odds with the data.

Credit:

Office of Bernard Sanders

Bhattacharya also acknowledged that the US suffers from large health disparities between different racial groups. Yet grants funding studies of those disparities were cut during DOGE's purge of projects it labeled as "DEI." Bhattacharya was happy to view that funding as being ideologically motivated. But as lawsuits have revealed, nobody at the NIH ever evaluated whether that was the case; Matthew Memoli, one of the other speakers, simply forwarded on the list of grants identified by DOGE with instructions that they be canceled.

Bhattacharya also did his best to portray the NIH staff as being enthused about the changes he's making, presenting the staff as being liberated from a formerly oppressive leadership. "The staff there, they worked for many decades under a pretty tight regime," he told the audience. "They were controlled, and now we were trying to empower them to come to us with their ideas."

But he is well aware of the dissatisfaction expressed by NIH workers in the Bethesda Declaration (he met with them, after all), as well as the fact that one of the leaders of that effort has since filed for whistleblower protection after being placed on administrative leave due to her advocacy.

Bhattacharya effectively denied both that people had suffered real-world consequences in their jobs and funding and that the decision to sideline them was political. Yet he repeatedly implied that he and his allies suffered due to political decisions because... people left him off some email chains.

"No one was interested in my opinion about anything," he told the audience. "You weren't on the emails anymore."

And he implied this sort of "suppression" was widespread. "I've seen Matt [Memoli] poke his head up and say that he was against the COVID vaccine mandates—in the old NIH, that was an act of courage," Battacharya said. "I recognized it as an act of courage because you weren't allowed to contradict the leader for fear that you were going to get suppressed." As he acknowledged, though, Memoli suffered no consequences for contradicting "the leader."

Bhattacharya and his allies continue to argue that it's a serious problem that they suffered no consequences for voicing ideas they believe were politically disfavored; yet they are perfectly comfortable with people suffering real consequences due to politics. Again, it's not clear how this sort of intellectual incoherence can rally scientists around any cause, much less a revolution.

Does it matter?

Given that politics has left Bhattacharya in charge of the largest scientific funding agency on the planet, it may not matter how the scientific community views his project. And it's those politics that are likely at the center of Bhattacharya's decision to give the MAHA Institute an entire afternoon of his time. It's founded specifically to advance the aims of his boss, Secretary of Health Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and represents a group that has become an important component of Trump's coalition. As such, they represent a constituency that can provide critical political support for what Bhattacharya hopes to accomplish.

Vaccine mandates played a big role in motivating the present leadership of the NIH.

Credit:

JEAN-FRANCOIS FORT

Unfortunately, they're also very keen on profoundly unscientific ideas, such as the idea that ivermectin might treat cancer or that vaccines aren't thoroughly tested. The speakers did their best not to say anything that might offend their hosts, in one example spending several minutes to gently tell a moderator why there's no plausible reason to think ivermectin would treat cancer. They also made some supportive gestures where possible. Despite the continued flow of misinformation from his boss, Bhattacharya said, "It's been really great to be part of administration to work for Secretary Kennedy for instance, whose only focus is to make America healthy."

He also made the point of naming "vaccine injury" as a medical concern he suggested was often ignored by the scientific community, lumping it in with chronic Lyme disease and long COVID. Several of the speakers noted positive aspects of vaccines, such as their ability to prevent cancers or protect against dementia. Oddly, though, none of these mentions included the fact that vaccines are highly effective at blocking or limiting the impact of the pathogens they're designed to protect against.

When pressed on some of MAHA’s odder ideas, NIH leadership responded with accurate statements on topics such as plausible biological mechanisms and the timing of disease progression. But the mere fact that they had to answer these questions highlights the challenges NIH leadership faces: Their primary political backing comes from people who have limited respect for the scientific process. Pandering to them, though, will ultimately undercut any support they might achieve from the scientific community.

Managing that tension while starting a scientific revolution would be challenging on its own. But as the day's talks made clear, the challenges are likely to be compounded by the lack of intellectual coherence behind the whole project. As much as it would be good to see the scientific community place greater value on reproducibility, these aren't the right guys to make that happen.

Read full article

Comments

The National Institutes of Health campus.

Credit:

The National Institutes of Health campus.

Credit:

Bhattacharya's claims that no funding had been cut appears to be at odds with the data.

Credit:

Bhattacharya's claims that no funding had been cut appears to be at odds with the data.

Credit:

Vaccine mandates played a big role in motivating the present leadership of the NIH.

Credit:

Vaccine mandates played a big role in motivating the present leadership of the NIH.

Credit: